Nantucket Needs Workforce Housing

The seasonal community struggles as the ratio of tourists to workers climbs.

Nantucket’s median home price is $4 million. Suffice to say, it’s not an affordable place. In fact, the island is one of the least affordable places in the world. You might be thinking, “Well it’s Nantucket, a rich outlier. It’s not comparable to a regular town.” In truth, Nantucket is the canary in the coal mine of housing affordability, and for this reason it’s worth studying. It became a victim of its own success. As a Nantucket native I regularly see hard-working friends, and sometimes family, get pushed out of town. If your community can avoid the situation we found ourselves in, they should. Some challenges are already lurking in your local bylaws.

So what caused housing to become so incredibly unaffordable on Nantucket? A whole lot of things.

Over half of the land is in conservation, which both increases the appeal of buildable land and constricts its supply. An airport allows for half hour $150 round-trip flights from Boston and New York, among other wealthy metropolises. The island’s ambitious Chamber of Commerce rallies the community around such events as “Daffodil Weekend,” in April, and “Christmas Stroll,” elongating the shelf life of seasonal second homes. On top of all of this, a rich history, preserved by a Historic District Commission, creates a strong identity and sense of place. And, of course, it’s an island with finite land (barring land reclamation, a story for another day). There is a common thread here: a supply-demand imbalance. People love Nantucket and there is not a lot to go around.

For a long time, the island’s housing situation was tough, but manageable. Then came Airbnb. Airbnb allowed every homeowner to tap into the island’s tourism bonanza. While renting homes to tourists is an old practice, Airbnb injected it with steroids. Short term rentals, or STRs, used to require building a relationship with a local homeowner. The homeowner was trusting you with their home, after all. This can now be done between strangers with a click, facilitated by Airbnb’s insurance coverage and a public guest rating system. As a result, tourism that was previously kept to hotels in commercial districts spread to residential neighborhoods. Studies confirm a causal relationship between Airbnb and the housing crisis – see this, this, and this. Like a gold rush, the STR opportunity brought a dog pile of investors. They converted homes to STRs which is further exacerbating demand.

Airbnb can be a gift to struggling towns with surplus housing stock, but Nantucket is not one of them. Until housing–and specifically workforce housing–is unblocked by zoning, Airbnb remains an opponent to housing affordability.

Regulating or banning Airbnbs has been the island’s hottest political topic for years. When resources are limited, politics follows. Fast forward to today and a severe labor shortage threatens the island’s basic services. The school system, police and fire departments, home services, and other critical operations are struggling to find staff. A commissioned review of the Nantucket Fire Department reached a disturbing conclusion, “the grave reality is that the current levels of manpower are going to kill firefighters; if not sooner than later.”

So here we are, with $4 million houses and a depleted workforce. In the face of high demand, isn’t it obvious to, you know, increase supply?

Yes, but not just any supply will do. Excluding a 300-person village on Martha’s Vineyard, Nantucket is the fastest growing town in Massachusetts. The housing supply and population have already been rapidly growing since the 1980s. Yet we are in a housing crisis in 2024. The problem is new homes built on Nantucket become second homes. The supply and demand orthodoxy broke. Second homes require but do not provide labor. By simply increasing the volume of housing, Nantucket chases its tail. It is workforce housing that needs to be built.

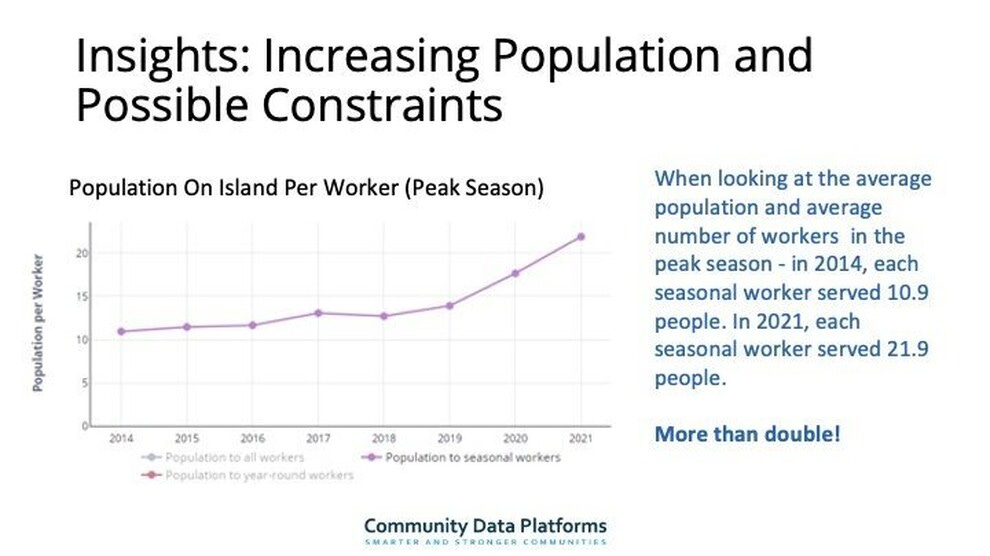

Nantucket needs to expand the ratio of workers to tourists by promoting workforce housing.

While creating year-round homes has been a popular rallying cry on Nantucket, there’s nothing wrong with a seasonal workforce. Nantucket’s population booms 4x in the peak of summer. Does it make sense to have a fixed supply of workers with a hyper variable supply of tourists? When facing a challenge at this scale it’s important to row in the same direction. The longer a community goes without addressing this problem, the more daunting it gets. Nantucket, a town of 15,000, has allocated $84 million to affordable housing to date.

Achieving equilibrium does not need to cost taxpayers. Nantucket’s Covenant Program lets homeowners subdivide their lots beyond what is otherwise allowed. In exchange, each new lot is restricted to buyers making up to 150% of Nantucket’s median income - $205,594 for a family of four. Owners must also spend ten months of the year in the unit. The program is a step in the right direction, but only creates about four workforce units a year. It also discriminates against high-earning residents. By instituting income maximums, those hopeful to find housing on Nantucket are incentivized to limit their work–or worse, forgo reporting income entirely.

Vail, Colorado created an elegant solution to their seasonal housing struggles. The municipality purchases deed restrictions that require occupants to work in the county thirty hours each week. That’s it. There is no appreciation cap discouraging participation nor income restrictions discouraging work. Vail, a town of 5,000, protected 40 units per year in its first four years. The average participating homeowner received $69,000 for the deed restriction. Combining a focused Vail-style deed restriction with Nantucket’s density benefit could create much needed workforce housing without tax outlays.

There are several more housing policy changes and programs needed to correct the course, a topic for coming weeks.

More workforce housing makes a balanced, easier Nantucket possible.